The United Nations is hurtling toward a severe financial crisis, threatening the stability of its core functions amid mounting deficits, delayed payments, and looming threats by the United States to terminate funding entirely.

Without decisive intervention, the UN risks insolvency, potentially leaving it unable to meet payroll obligations to staff and vendors by late 2024 and halting compensation for peacekeeping forces by mid-2025, according to The Economist.

On May 5th the UN will brief members on a previously unreported $600m (17%) cut to its $3.7bn budget aimed at avoiding default this year. It will include a hiring freeze while officials consider further savings that a Western diplomat describes as “moving jobs from New York to Nairobi”. Yet it may not be enough. A combination of deadbeat members and mad budget rules have led to a liquidity crisis. Now, a leaked White House memo proposing that America stop paying its mandatory contributions threatens a financial crash in the citadel of peace and security.

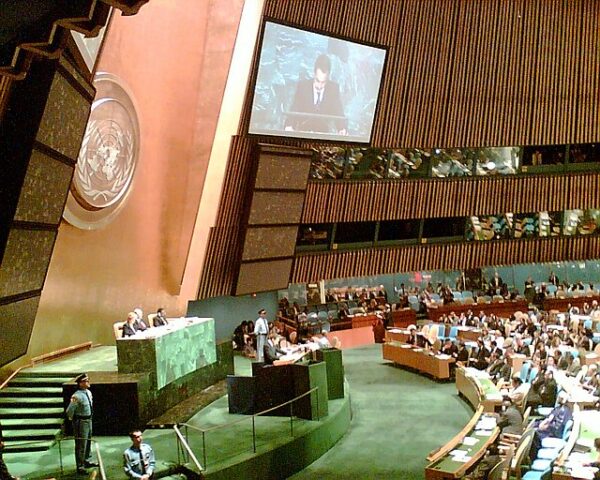

Last year the UN had a $200m cash shortfall, despite spending only 90% of its planned budget. This year will be much worse. Internal modelling suggests that the year-end cash deficit will, without cuts, probably blow out to $1.1bn, leaving the UN without money to pay salaries and suppliers by September. Most UN funding, such as for bodies providing humanitarian food or shelter, is voluntary, but the core functions are paid for through mandatory dues, linked to the size of members’ economies. These core functions include General Assembly meetings, peacekeeping and human-rights monitoring. In a letter seen by The Economist that Mr Guterres sent to members in February, he warned that the peacekeeping budget to pay for troops may run dry by mid-year.

The “root problem”, according to the UN boss, is that some members are paying their bills late and others not at all. The UN collects mandatory dues in the year that it intends to spend them. For that reason, members are meant to send their fees in January so that the UN can pay its staff and suppliers. But countries are paying their required fees later and later. In 2024 about 15% of the UN’s budget funds arrived in December. Then there are the free-riders. Members failed to pay $760m in mandatory contributions. The unpaid millions were owed by 41 countries, including America, Argentina, Mexico and Venezuela. Some may have paid after the year ended.

This year just 49 countries paid on time, forcing the UN to trim outlays and defer payments. The savings range from the quotidian (air conditioners will be set at 26°C in Geneva this summer) to the grave, such as slowed investigations into atrocities in Sudan and Ukraine. Targeted spending cuts to inefficient programmes or an overall reduction in the budget require a consensus vote among members, but poor countries are loth to cut an organisation they benefit from and which is paid for chiefly by rich ones.

In response, the UN has already announced a drastic 17% reduction to its $3.7 billion operating budget. Hiring is frozen, and UN peacekeepers may begin going unpaid in mid-2025—a dire situation foreshadowed by Secretary-General António Guterres in February.

Complicating matters further is a leaked memo from the Trump administration, proposing to terminate all mandatory U.S. contributions to the UN and affiliated organizations, including NATO. This proposal, wrote The Daily Caller, also includes dramatic reductions—54% cuts to humanitarian assistance and 55% reductions to global health funding. While these measures await congressional review and approval, their mere existence underscores the severity of the threat to the UN’s finances.

Moreover, former President Trump escalated tensions earlier this year by signing an executive order directing the U.S. government to initiate withdrawal from the United Nations altogether, while also reevaluating American participation in multiple international institutions.

The UN’s financial model is reliant on mandatory contributions from its member states, scaled to the economic size of each country. The U.S. and China, as the largest contributors, each fund about 20 percent of the organization’s budget. Yet China’s recent delinquency in payments, as it faces its own internal difficulties, has exacerbated the UN’s financial problems.

[Read More: Mainstream Media Goes After Another Conservative Woman]